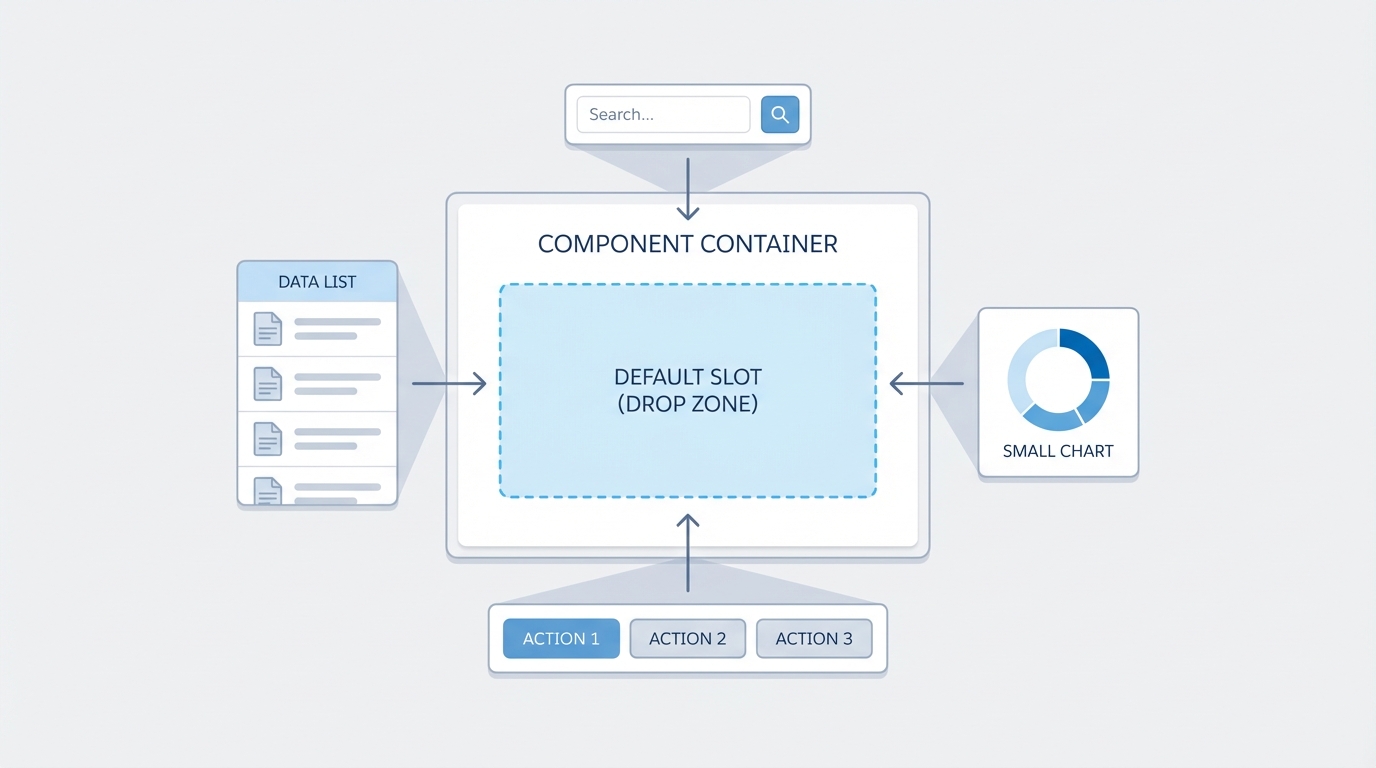

If you’re tired of building rigid components that break the moment a requirement changes, you need to master LWC slots. Basically, LWC slots are placeholders that let a parent component inject its own markup right into a child component, making your code way more flexible.

I’ve seen teams struggle with massive components that have twenty different @api properties just to hide or show certain buttons. It’s a maintenance nightmare. Instead of hard-coding every possible variation, I use slots to let the parent decide what goes where. It’s all about building a shell and letting the consumer fill in the blanks.

Why I always reach for LWC slots

Think of a slot as a “reserved seat” in your component’s HTML. The child component defines where the seat is, but the parent component chooses who sits there. This is a massive help when you’re trying to build a progress bar or a card that needs to look different depending on whether it’s on a dashboard or a record page.

There are two types you’ll use: unnamed (default) slots and named slots. An unnamed slot is the catch-all. If the parent passes content without a specific destination, it lands right there. Using unnamed LWC slots is the easiest way to start making your UI primitives reusable.

// cardComponent.html

<template>

<div class="slds-card">

<div class="slds-card__header">

<h2>Standard Card</h2>

</div>

<div class="slds-card__body">

<! - Anything the parent sends will show up here - >

<slot></slot>

</div>

</div>

</template>

Taking control with named LWC slots

Now, here’s where it gets interesting. Sometimes a single placeholder isn’t enough. If you’re building something like a modal, you need specific spots for a header, a body, and a footer. This is where named LWC slots come into play. You just give the slot a name attribute, and the parent targets it using the “slot” attribute on its own elements.

I use this pattern for almost every layout-heavy component I build. It keeps the CSS inside the child component consistent while giving the parent full control over the actual data and actions. It also makes LWC component communication much cleaner because the parent keeps the logic for the buttons it’s injecting.

// modalComponent.html

<template>

<section class="slds-modal slds-fade-in-open">

<div class="slds-modal__container">

<header class="slds-modal__header">

<slot name="header">

<h2>Default Title</h2>

</slot>

</header>

<div class="slds-modal__content">

<slot></slot> <! - Default unnamed slot for body - >

</div>

<footer class="slds-modal__footer">

<slot name="footer"></slot>

</footer>

</div>

</section>

</template>

Checking if a slot is empty

One thing that trips people up is trying to hide a wrapper div if no content was passed to a slot. You can’t just use an “if:true” on the slot itself. You have to go into the JavaScript and use assignedElements(). I’ve used this many times to hide a footer section entirely if the parent didn’t provide any buttons. It keeps the UI from looking clunky with empty white space.

// modalComponent.js

get hasFooter() {

const footerSlot = this.template.querySelector('slot[name="footer"]');

return footerSlot && footerSlot.assignedElements().length > 0;

}

Pro Tip: Always provide default content inside your slot tags. It acts as a fallback so your component doesn’t look broken if someone forgets to pass content to it.

Best practices from the field

- Keep your slot names simple and descriptive like “header”, “actions”, or “sidebar”.

- Don’t go overboard. If you find yourself adding ten slots to one component, you might actually need to break that component down into smaller pieces.

- Remember that styles in the parent component don’t automatically bleed into the child, but the content inside the slot is still technically part of the parent’s DOM tree.

- Use conditional rendering in the child to handle empty slots gracefully so you don’t end up with weird margins or borders.

Key Takeaways

- LWC slots are the best way to handle content projection and build truly reusable UI primitives.

- Named slots give you multiple injection points for complex layouts like modals or grids.

- Slotted content stays in the parent’s context, which makes event handling and styling much more intuitive.

- Use

assignedElements()in your JS if you need to detect whether a slot actually has content.

So, the next time you’re about to add yet another boolean property to a component just to show a specific icon or button, stop. Try using LWC slots instead. It’ll make your components much easier to maintain, and your fellow developers will thank you for not making them hunt through a mountain of props just to change a bit of text. Give it a shot on your next project and see how much cleaner your code gets.

Leave a Reply